15/02/2018

In recent years, thanks in large part to successive technological advances, productivity has skyrocketed. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) levels never seen in history are reached, but they do not reach the “real people”, who see their salaries stagnate. Inequalities are growing and, if political and social upheaval is to be avoided, a new social contract must be reformulated as a matter of urgency. It is the challenge of governing abundance.

This is how the Dean of the IE School of International Relations defined the current situation, Manuel Muñiz, who gave a lecture on Technological revolution and fracture of the social contract’ in the series of debates Mornings of Tomorrow’ organized by Asociación Digitales to analyze the political and social changes facing society today due to the technological revolution.

He also holds a PhD in International Relations from Oxford University and analyzed the main challenges posed by the technological revolution: the transformation of the labor market and the stagnation of incomes and increase in inequality.

Muñiz downplayed the importance of the former because, although he provided projections that 47% of current jobs are at risk of disappearing, he contrasted this with others that claim that only 10% of current jobs will disappear, while 30% will be transformed.

However, he emphasized the dangers posed by the polarization of the labor market, where there is a sharp drop in employment generation in the middle sector. “Wealth is accumulated in 1% of the population. Inequality levels in the U.K. are similar to 1,850, while in the U.S. they are the same as in 1929.” he said.

“Since 1970,” he explained, ” productivity has become disconnected from labor income. Productivity increases and therefore indicators such as GDP or global wealth, but not wages. It is the end of the social contract.

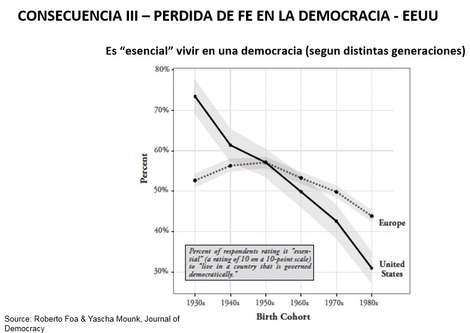

In his opinion, this has three main consequences: pessimism, support for anti-establishment forces and loss of faith in democracy. Muñiz asserted that, contrary to what some have pointed out, it is not the increase in immigration that has provoked support for new political movements, but rather the increase in the precariat. “It was in more culturally diverse cities like London that the rejection of Brexit was strongest,” he recalled.

The dean of the IE School of International Relations remarked that it is the economy that determines political behavior. “Whoever believes that the economy is doing well, trusts their institutions. Whoever believes that the economy is going badly, does not trust them. There is a direct correlation between rising unemployment and the rise of populism or support for leaving the EU,” he said.

In terms of solutions, he pointed out 4 lines of action as a possible solution to a model that is being questioned by the younger generations. Only 30% of millennials in the U.S. considered it essential to live in a democracy, compared to 80% who did in 1930.

The first of these is education, in which he opted to reinforce digital skills and underpinned with data the direct correlation between higher income levels and greater knowledge of the digital environment. Secondly, he pointed to the recalibration of the tax burden so that it is applied not on labor but on capital and is understood in global terms, which he defined as a participatory approach.

The third axis is a new redistributive policy that deepens the welfare state, while the fourth involves redefining the role of the private world, giving companies a role that goes beyond generating profits for their shareholders. In short, a new social contract that responds to the challenge of governing in abundance.