02/10/2018

It is absolutely impossible to describe the future that is yet to come. Just look at the many science-fiction movies of the 1970s and 1980s, for example, where flying cars and hoverboards were the order of the day, but no one talked about the Internet.

However, it is possible to anticipate or foresee how our lives will change by looking at what disappears. Just as video stores, the USSR or the fax machine are part of the past, so will soon be such everyday things as money, work, stores, oil or flyers.

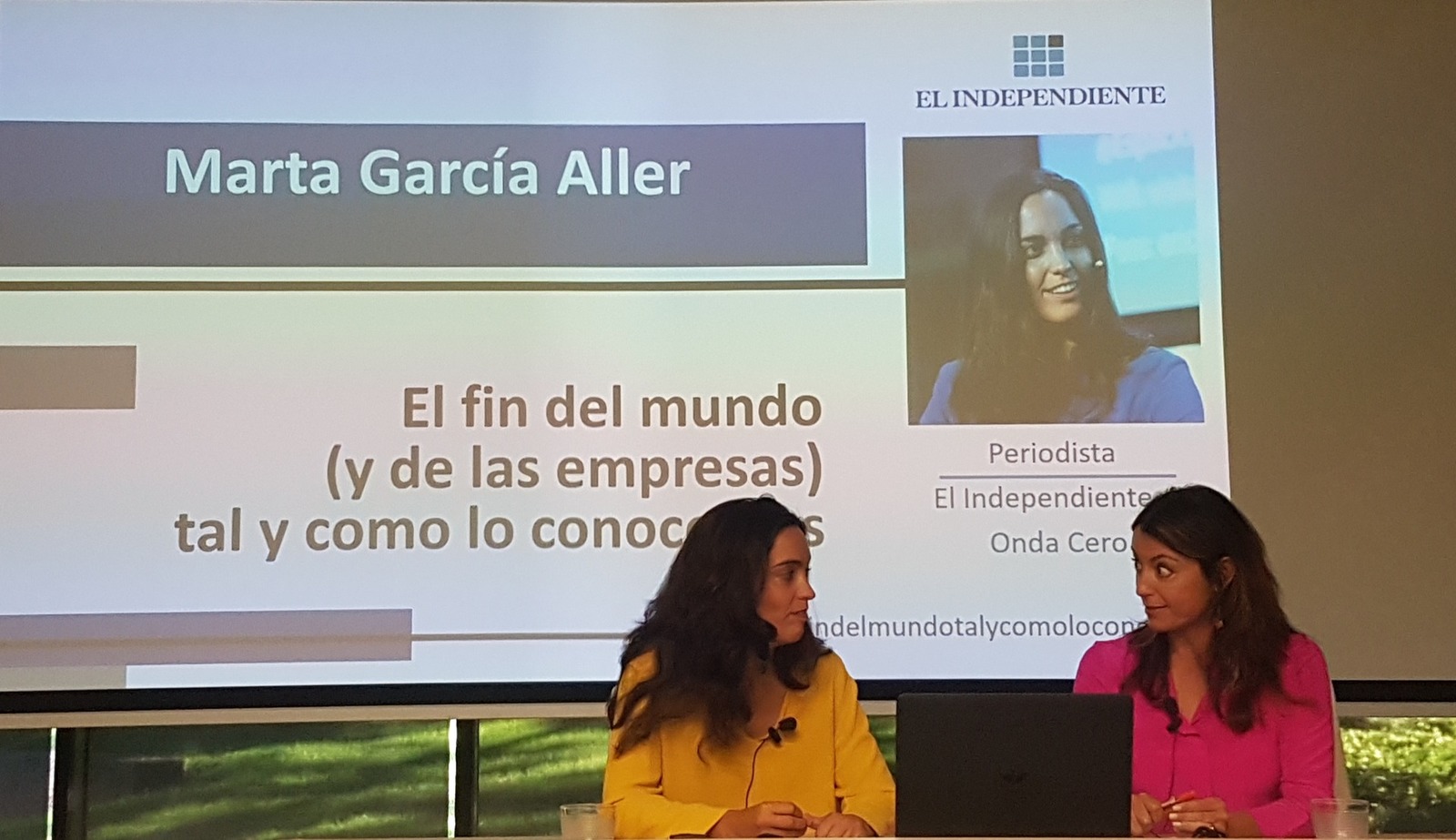

On this premise, Marta García Aller has written ‘The end of the world as we know it’, a book that has become one of the best-selling non-fiction books in Spanish and that served as a prelude to the debate in the breakfasts organized by DigitalES, Las mañanas del Mañana.

The DigitalES breakfast guest also reviewed many other endings. That of flyers – which he dated to the 1940s – that of oil – superseded by new forms of energy – that of stores or that of money, which will bring with it the end of queues by eliminating payment points, the most painful process of a purchase.

He also warned that the process of approaching technology will follow a pattern similar to a child’s learning, first through the hands, then the voice. “We have learned to use the touch function of smartphones, but more and more we will do it with voice,” he said.

During the event, the journalist of El Independiente launched, as he does in his book, a series of reflections with the aim of inviting attendees to think about an increasingly near future in which “datification”, or the extension of data, will have an impact similar to that produced in its day by electrification.

“We are already cyborgs,” says García Aller, “The smartphone is part of our memory, of our capacity for conversation. Today they are an external part, but they are already the prelude to the technology that will be implanted in our bodies”. “The technology that succeeds is not always the best, but the most comfortable, the one that makes our lives easier,” he added, referring to wearables.

Another of the points he insisted on was what he called the end of things. “A teenager does not understand that the contents of the past were objects and were not updated on the fly, like the Larousse encyclopedia.” “Now we no longer want to buy objects, but services, to pay for use and not for ownership. Having a car as a symbol of freedom is naive and old-fashioned, now younger people don’t want to have a car, they want to use it,” he explained.

“Even programmed obsolescence is becoming obsolete. We no longer want objects, but services, because the cool thing is not how much you have, but how many things you do,” he said after stressing the importance of social networks to communicate precisely everything we do.

He also pointed out that technology is already producing modifications in the human brain: the capacity to consume information increases but attention decreases. “And also in behavior. Empathy decreases with the use of WhatsApp, since by not seeing the reaction of the recipients of the message we dehumanize ourselves,” he added.

The journalist also wanted to appeal to the responsibility of technology companies in the 21st century. “Some of the dangers of its use, such as sending WhatsApp while driving, should be controlled,” he said.

Finally, he stated bluntly that privacy, a product of the industrial age and life in big cities, is going to disappear. “But it should not be mythologized either. When people lived in villages it didn’t exist either, and in a connected society it is more than likely that it will end,” he concluded.